Georgia on my mind (‘cause it’s a cautionary tale)

The lesson from Georgia: When state lists are a mixed bag, districts pick the weaker stuff.

Curriculum reform was a key pillar of Georgia’s 2023 Early Literacy Act (which also introduced teacher preparation audits, screening, and teacher training). The legislation required the Georgia Department of Education (GDOE) to vet elementary reading curricula and create a list of high-quality options. Then, districts were required to select a program off the list or secure state approval for the “supplemental bundle” used in schools.

GDOE’s board created a committee to create the curriculum list, including teachers from across the state as well as GDOE leaders and curriculum specialists.

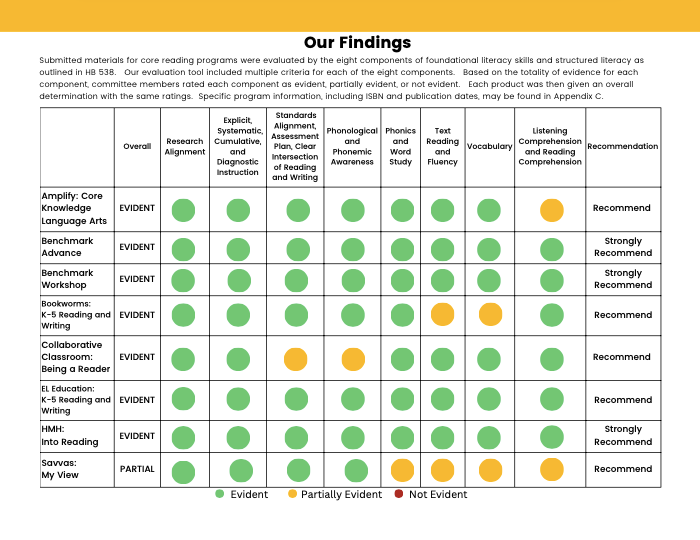

It published its recommendations in September, 2023:

Many in the field groaned. The committee hadn’t screened for knowledge-building or text complexity, and it showed. The “strongly recommended” options were basals from big publishers that fell short on text quality/complexity and knowledge-building. Strangely, EL Education was the only program to receive all-green evaluations but no “Strongly Recommend.” (EL Education was developed by a nonprofit and it’s distributed by another nonprofit, Open Up Resources. Neither has the resources to send lobbyists to state houses, which might be the culprit.)

Other details didn’t make sense to anyone who knew these programs: Why was Bookworms getting dinged for text reading and fluency when it has the most books of any elementary curriculum on the market, and choral reading is a mainstay of its lessons? Why was CKLA dinged for reading comprehension when it’s arguably tailor-built for comprehension, and it has a number of RCTs to show its effectiveness1? Where was Wit & Wisdom?

But, we hoped districts would make smart choices, even as the Georgia list kept evolving to add more big publisher options like Wonders.

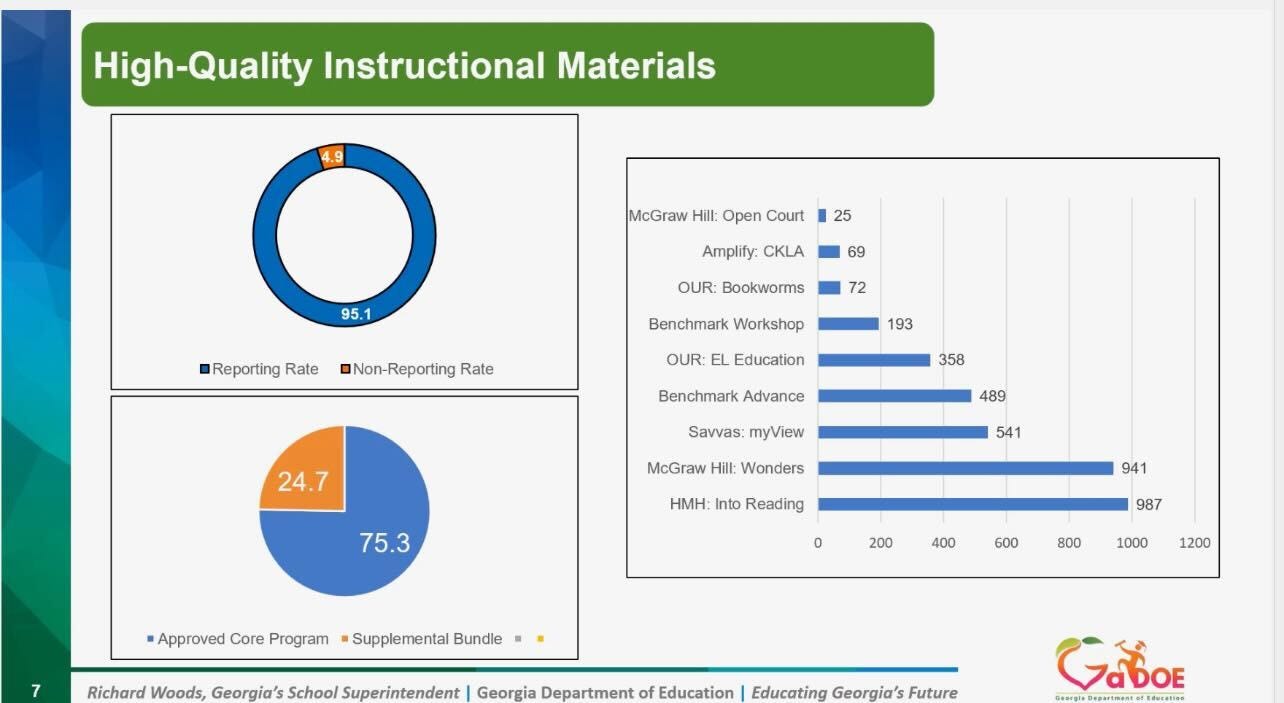

This week, Georgia reported on curricula used in its schools:

Sadly, Georgia districts didn’t select the best options. Among districts using approved programs, most selected basals. The programs with stronger evidence of efficacy (CKLA and Bookworms2 with standout performance in studies, EL Education with frequent use in top-performing states Louisiana and Tennessee) have much less traction in Georgia.

A quarter of districts use approved “supplemental bundles.” This isn’t always bad: it includes districts using Wit & Wisdom, a strong curriculum designed to be paired with a foundational supplement. Also, Georgia has banned materials with three-cueing. None the less, that 25% is a black box.

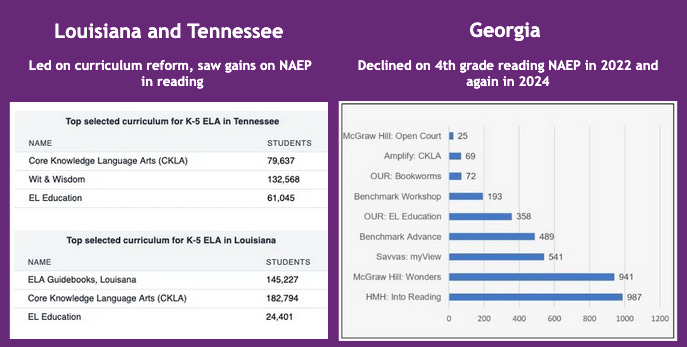

Here’s the biggest concern:

The curriculum used in Georgia have little in common with the curricula in Louisiana and Tennessee, the two states with surging reading outcomes. That matters – a lot.

Here’s a side-by-side:

Georgia offers a critical lesson to the field: When state lists are a mixed bag, districts pick the weaker stuff.

Locals make an important point: these lists are quickly turned into marketing campaigns by the corporate publishers, which enjoy a historic edge on sales & marketing; in fact, the ‘marketability’ of basal programs is their calling card.

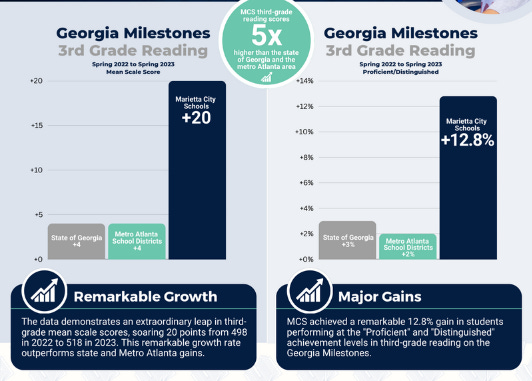

Georgia has positive stories in districts that selected strong materials. In Marietta City Schools, investments in structured literacy have paid off. Marietta invested in well-trained reading specialists in 2021, and by 2023, it was outpacing the state in reading gains by a factor of 5. Unsurprisingly, Marietta made excellent curriculum choices, adopting Wit & Wisdom in 2024, paired with UFLI for foundational skills. The smart curriculum selections are part of a broader effort: Marietta provides intervention during the school day for underperforming students and it has piloted after-school tutoring for struggling third graders. Its “success spans across all demographics. Black, disabled and economically disadvantaged students all saw double-digit gains in proficient literacy rates.” You love to see it.

Mind you, Marietta’s outsize success hints at the limited progress in the average Georgia district. Statewide, Georgia hasn’t rebounded from the pandemic.

Ultimately, Georgia is a case study in implementation failure–stalled reading scores in spite of passing reading legislation in 2019, 2023, and 2025. Not only have most districts selected mediocre programs, they’re apparently also dragging their feet on state-mandated training. In addition, local advocates worry about the mixed-quality state screener list.

Georgia adds to concerns about state capacity to create curriculum lists, already in question over recent moves in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and more. Questions persist about district decision-making, too; the Massachusetts legislature is likely to take local control away from districts this year where curriculum selection is concerned. Still, shifting power to state leaders comes with real risks, since states keep fumbling their curriculum lists.

Locals make an important point about the lists: they are quickly turned into marketing campaigns by the bigger curriculum publishers, which enjoy a historic edge on sales & marketing. In fact, they seem to put product marketability ahead of product quality.

Many advocates behind the bill are not happy.

“We have been advocating for high-quality instructional materials to anyone who will listen. It took legislation to move the ball forward, and the state is still promoting materials with inconsistent quality,” said Tina Engberg, a leader of Decoding Dyslexia Georgia until recently.

Engberg worries that the state is caving to lobbying by superintendents and vendors. “I wish more people understood how this is all going down behind the scenes. Lobbyists have a lot of power.”

Missy Purcell, a fellow advocate and former teacher, echoed the concerns. “If we keep allowing districts to have local control loopholes, we will never see change.”

The devil is in the details, and the devil can be found in Georgia’s execution. Purcell points out that Georgia’s “Inspire” website features 400 different resources. “Are all those resources aligned to the curricula? Does anyone have time to comb through 400 resources?,” she asks. Excellent questions.

As reformers chase Southern Surge replication, these implementation woes will keep Georgia on my mind.

Notable studies of CKLA include the Grissmer study and a study by Sonia Cabell and HyeJin Hwang.