How book-rich, knowledge-rich curriculum is fueling the Southern Surge

Louisiana and Tennessee brought "knowledge-building," book-centered curriculum into statewide use, and reading gains followed.

Fun fact: Louisiana and Tennessee are the only two states in the country where book-rich, knowledge-rich curriculum is used statewide – and both saw gains in reading proficiency after these materials entered schools.

These Southern Surge states offer important evidence that curriculum can be a catalyst for better reading outcomes, and that knowledge-lite, ‘passage popcorn’ curriculum is a problem.

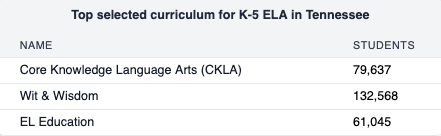

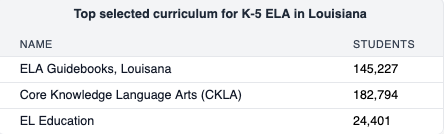

The best window into curriculum use is the Center for Education Market Dynamics (CEMD)1. In Tennessee and Louisiana, these are the most-used programs:

Each of these programs – Core Knowledge, Wit & Wisdom, Louisiana Guidebooks, and EL Education – incorporates whole books. That would seem to be the most ho-hum statement one could make about reading curriculum, except it isn’t standard in US classrooms.

As I recently reported, book-light curricula are common in American schools. Wonders, which is entirely devoid of chapter books in grades 3-6, enjoys remarkable popularity:

Wonders is used in nearly 20% of elementary schools in America. In California, Wonders is the second-most-used curriculum in elementary schools and the third-most-used curriculum in middle schools. It’s the most-used elementary curriculum in Florida, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Colorado, Arizona, Utah, and Idaho; the second-most-used in Minnesota, South Carolina, New Mexico, West Virginia, and South Dakota; and the third-most-used in Texas, Indiana, and Kentucky.

When you poke around CEMD’s Market Explorer, you find that book-lite ELA curricula, such as the popular Into Reading program, are prevalent in virtually every other state. Only Tennessee and Louisiana2 have achieved consistent use of excellent materials. It wasn’t an accident – leaders used a thoughtful mix of incentives and policies to establish this norm.

Mind you, the curricula used in LA/TN aren’t just book-rich. Usually, they are described as “knowledge-building” curricula3, because they were also designed to incorporate science and history content. Knowledge-building programs have a number of common characteristics:

The reading and lesson activities focus on science, history, and arts topics, because research shows that students’ knowledge and vocabulary in these domains drives their reading comprehension.

All students work with texts at or above grade level, including students who are reading below grade level, which is show to work better than common alternatives.

Reading and writing are connected. Students do daily writing exercises related to the content in the reading lessons. This allows students to focus their cognitive energies on the writing craft, and it supports retention of the new knowledge.

Vocabulary and reading strategies instruction are incorporated into work with whole books and also paired texts (articles, poems).

All of that is good, and aligned to both research and standards4.

What’s less-good: these materials are only used in a third of American schools, at most. Reform efforts aim to increase that share.

The case for those curricula now runs through BBQ Country:

Louisiana and Tennessee made book-centered, knowledge-rich curriculum a statewide standard, and their reading outcomes rose during an era of national decline.

State-scale evidence is a really big deal, so this is a game-changing insight.

It offers a response to the growing national concern about books (and writing!) disappearing from education5.

It puts pressure on conventional narratives in K-12 education, such as “Passage-heavy programs are the way to prepare kids for state assessments.” In fact, it was a break with passage popcorn programs that propelled Louisiana and Tennessee’s gains.

And maybe, just maybe, it can take the heat out of the Reading Implementation Wars6.

Can State-Scale Evidence Quell Debate?

Some aren’t bought into knowledge-building ELA curriculum, even as study after study after study has validated the approach. Doubts have persisted in some quarters, even within the Science of Reading community.

To my surprise, some have questioned the evidence for books in English Language Arts. I cannot believe I just typed that sentence.

My response is simple:

Louisiana and Tennessee dispel any doubts about knowledge-rich, book-centered curricula. We should sing that story as joyfully as Dolly Parton in church on Sunday.

And the choir must be heard nationwide. Big state curriculum lists are in play right now: California just passed legislation that will spawn a new state list. Massachusetts is poised to embrace historic curriculum mandates. Pennsylvania’s curriculum list train wreck needs a cleanup.

We must help states avoid implementation failure on curriculum, because districts keep programs for 5+ years. Today’s curriculum signals will be felt in schools for the next decade.

How Did They Do It?

In Louisiana and Tennessee, statewide adoption of quality materials emerged from strong leadership and people-centered programs. Having a good curriculum list is where the work begins, not where it ends.

The goal is well-supported teachers who understand and embrace the new materials. In Tennessee, 96% of teachers reported that they primarily used the materials adopted by their districts. It’s unprecedented, and everyone should know how it came to pass.

In Part II, we’re going deeper into the LA/TN stories, to peel back the onion on the curriculum layer. It’s a people story, and a professional learning story, far more than a policy story.

In Louisiana, we’ll hear from John White, the innovative superintendent of education (2012-20), as he describes 8,000-teacher conferences as “curriculum revival meetings.” And Whitney Whealdon, lead author of Louisiana’s Guidebooks curriculum, on how she co-created materials with teachers.

Plus advocate Kelli Bottger, who explains that Louisiana “hasn’t let their foot off of the gas” on the curriculum efforts, 13 years into the effort. Today, LDOE announced new screening gains. It’s working!

We’ll hear from Penny Schwinn and Lisa Coons in Tennessee, about their intentional efforts to be good “shoulder partners” to districts, and how they built celebrations into the work as much as “sticks.” I’ll explain why I consider their work to be the new national model.

We’ll hear from educators, too, because the educator experience of state reforms is frankly the most important story of all. Coming soon in Part II.

Spoiler: Leadership eats policy for breakfast.

Related Reading

In “My Kingdom for a Reliable Curriculum Review”, Holly Korbey captures the “frankly bananas” review landscape.

Please check out “Why have books disappeared from many ELA curricula?” if you haven’t. Matt Yglesias shared it in his excellent column on declining national outcomes in September, along with two other pieces from my Substack (!).

Caitlin Goodrow penned an astute tribute to curricula with whole-class novels. It illustrates the teacher embrace of these materials.

Center for Education Market Dyamics is our best source, even though it only covers a sample of US districts (currently it reflects 2,700 districts, and we have 13,000+ nationally). Don’t get me started about the limited insight into curriculum usage in the US.

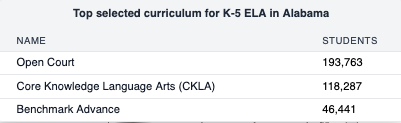

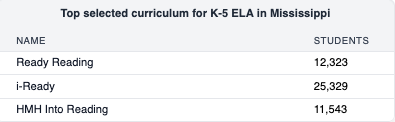

Across the country, you’ll find at least one and sometimes three lesser programs on the most-used list in every state outside LA/TN. Even Mississippi and Alabama are still working on curriculum reform. Here are the top programs in those states, noting that it’s a smallish sample in Mississippi (representing approximately 26% of Mississippi schools):

As I have written previously, these states have phased in curriculum reforms. Some believe that Mississippi’s 8th grade gains have lagged its 4th grade gains because it needs to address this gap.

There’s a whole oral history about how these materials came to be called “knowledge-building” curricula. It starts in the Common Core era, when a number of providers, including nonprofits, developed new curricula to help schools meet the new, higher standards. Literacy leaders proclaimed a “curriculum renaissance.“

The term “high-quality instructional materials” or “HQIM” was coined to describe curriculum aligned to the Common Core standards. People came to use this term interchangably with curricula that earned “all-green” reviews from EdReports, which reviewed for standard-alignment.

Then EdReports began issuing questionable reviews, so HQIM was no longer a good marker of quality. The field needed another way of separating the legitimately-good programs from the weaker programs. (Note: the passage-heavy, book-lite basal programs were the weaker programs.)

At the time, a Knowledge Matters Campaign was underway, working to raise awareness of the role of background knowledge in reading comprehension. The campaign talked about the better curricula as “knowledge-building curricula,” and also put out a list of those programs. It was a better guidepost than EdReports.

The field gradually started using “knowledge-building curriculum” to distinguish between HQIM and better stuff. But other names for the category would have been equally valid. We could have called these programs "book-centered curriculum” or “whole class novel curriculum” or “daily writing curriculum” or “grade-level reading programs” or “Does All The Important Things” curriculum. They’d be equally valid labels.

I don’t mean to imply that these curricula are perfect. There is no such thing as a perfect curriculum, each has its own shortcomings, and we are witnessing ongoing innovation in the field as providers continue refining materials. The space evolves. I’ve been following trends in districts using these programs, and I notice that increasingly, districts are trading in the foundational skills components of knowledge-building programs for the viral and beloved UFLI materials. Regardless, even if the materials in this category aren’t perfect, they are head and shoulders above the alternatives. Let’s give teachers the best stuff.

We shouldn’t miss the role of the Common Core standards in this story. These materials were all designed to align to the Common Core “shifts.” One could argue that Louisiana and Tennessee are proof that the Common Core ELA reforms worked – when states actually bothered to design sustained systems around them (spoiler: most did not).

Academic concerns are a trending topic. Last year, “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books” went viral. This year, the New York Times is investigating the disappearance of books from schools.

Derek Thompson worries that AI will outsmart us because reading and writing skills are in decline. Idrees Kahloon explores the “low-expectations theory” for educational declines while proclaiming that “Americans are sliding towards illiteracy.”

As I write this morning, an alarming report from UC San Diego, one of the most competitive colleges in the University of California system, is flying around social media; it shows that 1/5 of freshmen are being placed in remedial writing courses.

The Reading Wars are over. No serious person disagrees about the need for systematic phonics to teach children how to read and the ‘whole language’ camp is more or less relegated to a dying breed in academia. However, there are still disagreements about how to teach reading. I have come to call these the Implementation Wars.

The Implementation Wars Era is just as tribal and exhausting as the Reading Wars era. One of the debates that just won’t die is about the value of knowledge-building curriculum. There are other debates, about whole-class vs small-group instruction, intervention models, and more.

Can the Louisiana and Tennessee stories settle one of these debates? For the love of God, I hope so.

Disclosure

I talk a lot about curriculum, so this is a good time for me to restate that I have no affiliations with the provider of any K-12 product, curriculum or otherwise, and I designed the Curriculum Insight Project to screen carefully for conflicts of interest.

I served as Chief Marketing and Strategy Officer at provider Open Up Resources from 2016-18 (one reason I know this space so well), and in past years, I proudly supported the Knowledge Matters Campaign’s efforts to raise awareness of this category.

The literacy space is tribal. Proponents of other approaches to reading instruction sometimes get personal, taking potshots at advocates for knowledge-building curricula; I have been smeared as being “just a marketer.” Here’s my response: if you you had traveled to pioneering schools, visiting kindergartens, chatting up teachers, and seeing this growth firsthand, so you knew how the Southern Surge was unfolding… would you ever stop talking about this stuff? Me, neither.

Thank you for this research and article.

Charlotte Mecklenburg County uses EL Education. I am extremely glad they are using whole books.

I substitute teach in elementary and middle schools (I was a former social studies teacher). The teachers, and I, find the curriculum soooooo boring and repetitive. It’s truly hard to discuss a non fiction paragraph about frogs for an hour. It’s even harder to return to that hour discussion and workbook page from I-Ready on their devices (also boring - but on the IPad).

The kids like the American Revolution section the best (4th grade).

“I am Malala” in 3rd grade, where the kids learn about bad vs good Muslims seems a bit deep and unnecessary for 3rd grade in the US. So yes, curriculum is better and evolving, but also has morals - environmental and political.

Couldn't agree more. It's amazing to see how much of a difference a truly knowledge-rich curriclum can make. How do we scale this impact?