For the antidote to sloppy skepticism about Mississippi, look to Louisiana

Tired of the Mississippi mistrust doom loop? Louisiana offers a counterweight. The Bayou State deserves more attention for its own smart model, anyway.

We have a new entry in the effort to debunk Mississippi’s success story. Howard Wainer, Irina Grabovsky, and Daniel Robinson, three “sceptical” statisticians, published a paper confidently proclaiming that Mississippi’s gains were a hoax: merely the selection effect from retaining low-performing students. The internet haters piled on.

The Skeptics focus on the mean (or statistical average) score and how it could theoretically rise as a function of lower-performing students being cut out of the distribution. A fancy graph invites us to behold what happens to the average score if a large share of low-performers fall out of the sample. It’s arithmetic!

The Skeptics ignored significant counterfactuals. Critically, they fail to note that Mississippi hasn’t just raised its average score. As Chad Aldeman and Kelsey Piper have noted, Mississippi’s scores are rising at all performance levels. The scores for its lowest-performers are up, and so are the scores at the 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles. That can’t be explained away by the state’s retention policy.

Also, the Skeptics fail to account for a rather important detail: where are those retained students going? Because the retained third graders continue to exist in Mississippi schools, so they should be showing up in future NAEP testing cohorts.

Let’s revisit the details of Mississippi’s approach: Schools are required to assign retained students to a high-performing teacher the following year (a seldom-discussed policy detail), and also to provide intensive intervention and support. The state requires best efforts for retained third graders in order to produce success on the state exam the following year, thus moving retained third graders up and into that fourth grade testing cohort1!

Mississippi’s retention policies have been in effect for a decade. I am unaware of any teenage third graders hanging out in Mississippi schools so they can be permanently erased from the state testing pool, or any other dynamic that would distort the sample over time in the manner implied by the paper.

Overall, the Skeptics make a sloppy argument by innuendo.

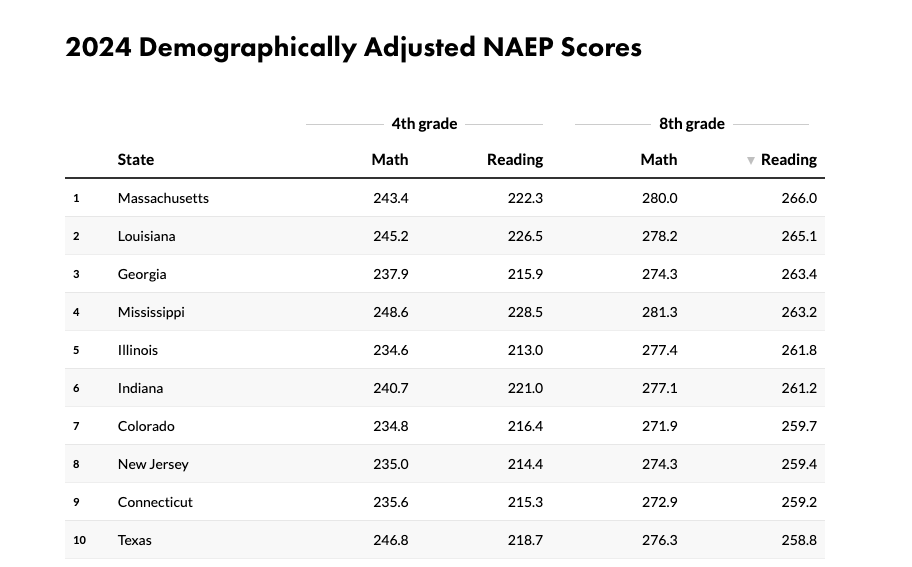

I could keep listing issues with the Skeptics’ paper, like their blatant misrepresentation of Mississippi’s math outcomes (which are actually quite solid; Mississippi is “16th in 4th grade math, 35th in 8th grade math, #1 in both categories” when adjusting for demographics). You can check the footnotes2 for more nit-picking if you’re into that sort of thing. Yet I think there’s a better use of time.

After all, the internet is full of credulous readers reposting a pretty bad paper as if it proves Mississippi’s malfeasance.

This mistrust isn’t new. In fact, it’s getting more irrational as Mississippi gains in each NAEP cycle. And it’s becoming repetitive. One might say the Skeptics’ paper is just Freddie DeBoer, But With Graphs and Equations. (Piper and I responded to DeBoer in October, giving a fair hearing to theories that Mississippi’s results might be overstated, in case you missed it.)

The lesson: some aren’t going to buy the Mississippi story, no matter what you say.

So, let’s look at the second-biggest gainer on the NAEP. Louisiana’s story is more clear-cut.

Louisiana’s Retention-Free Literacy Gains

Louisiana has the most growth on the NAEP in 4th grade reading since 2019 and the second-best reading proficiency in the nation for low-income 4th graders.

And Louisiana’s third grade retention law just took effect this year. None of Louisiana’s 2024 NAEP gains could be ascribed to selection effects.

Louisiana’s performance looks solid in eighth grade reading, not just 4th: its 8th grade reading performance has closed the gap with the US average, and it’s #2 for eighth grade reading in the Urban Institute’s demographically-adjusted rankings3.

Frankly, Louisiana’s work doesn’t get enough attention. Even Bayou State natives like Donna Brazile seem unaware of its shining star in literacy.

That’s a shame. I believe Louisiana—and its closest imitator, Tennessee (which also shows gains) —offer the most effective and portable models for reading improvement.

It’s worth unpacking the difference between Louisiana and Mississippi. While these states shared a common playbook, they had a different order of operations and tactics. “Louisiana followed Mississippi.” is a misunderstanding. Its reforms sprung from different sources, and looked quite different in the early years (which roughly paralleled Mississippi’s).

The Bayou State led with curriculum reform, actively encouraging districts to use programs designed to nurture reading comprehension, and training teachers to use this new ‘knowledge-building’ curriculum. State leaders organized informative conferences for educators, developed a mentor program to nurture local leadership, and redesigned state procurement and funding systems to align with reform goals.

Since 2021, Louisiana has layered on reforms focused on reading foundations: K-3 screening, teacher training on how kids learn to read, and most recently, 3rd grade retention policies.

Mississippi introduced 3rd grade retention from the jump, via 2013’s Literacy-Based Promotion Act (LBPA). It also led with teacher training and coaching. The bottom 20% of schools received intensive teacher training plus 2-3 days per week of literacy coaching. When scores in low-performing districts began to rise, demand for the subsidized training spread across the state. Mississippi also mandated K-3 screening for early reading skills, with parent notification of results.

By 2019, Mississippi began efforts to improve curriculum statewide, and in 2021, Mississippi changed from time-intensive, theory-heavy LETRS training to more efficient teacher training.

Both states did the same things, but with a different sequence and varied implementation. For example, Louisiana and Tennessee have been more successful introducing book-rich, knowledge-building curriculum statewide. Mississippi’s curriculum picture is still a mixed bag (and this probably explains some of Mississippi’s relative weakness in 8th grade).

To really follow the leaders, check out Tennessee for creative innovations on the Louisiana model. Tennessee leaders developed the most streamlined and widely-embraced training, offered stipends to teachers for taking the training, and nurtured incredible buy-in for curriculum change. Seriously… two years into Tennessee’s curriculum adoption, 96% of teachers were primarily using the programs selected by their districts. That’s unicorn-level embrace.

Like Louisiana, Tennessee introduced retention as a lagging reform (it went into effect in 2023).

For a number of reasons, the LA/TN models are more replicable—by states and districts. The curricula in their schools can be adopted anywhere. The teacher training options in Louisiana can be applied anywhere. The work didn’t historically rely on a state retention policy. You really could do this work in your backyard.

As long as Mississippi Mistrust reigns, Louisiana offers an antidote as satisfying as the Crawfish Étouffée at Mothers. Served with a side of Tennessee’s template.

It’s the Replication, Y’all

Mississippi and Louisiana’s approaches have both been replicated successfully by states with gains to show for it. Alabama followed Mississippi, as Tennessee mirrored Louisiana. These four states give us a promising playbook.

I cheer these successes and the replication potential, even as I acknowledge that education “miracles” have sometimes been frauds, and K-12 history is littered with short-lived successes. Accordingly, I worry that Southern Surge states may take their feet off the gas and regress. No rose-colored glasses here… but optimism, none the less.

Across the Southern Surge states, targeted investments in schools and teachers have increased reading proficiency for public schoolchildren. I can’t relate to instincts to reject that story.

But as the Southern Surge continues to gain attention, doubters gonna doubt and motivated reasoners gonna publish. The Skeptics’ Script is clear at this point: talk only about Mississippi, sow doubt with tales of EdReform failure, and oversimplify what actually happened (“just phonics,” essentially-just-retention policies).

The antidote is to talk about the trend, not the single-state stories.

This footnote from my piece with Piper is on point:

“I was, in fact, myself unsure how seriously to take the results in Mississippi until I saw the positive results from the other states imitating it. Improvements are good, but often don’t scale. What makes Mississippi exciting is that, when we imitate the things they did elsewhere, we also see improvements. With the “Texas Miracle,” as deBoer notes, efforts to copy the winning formula didn’t work because there was no real winning formula to copy. But efforts to copy Mississippi appear to be working.”

This speaks for most people, I think.

Preach the story in Louisiana and the evidence of replication, and we just might escape the Mississippi mistrust doom loop.

The Meme Version

Sometimes the meme says it better:

Related Reading

Every time I praise the Southern Surge, I also need to explain that this work isn’t replicating across the other 46 states—even in states that passed legislation or implemented policies in the last 5 years (which is all of them). Read more about the national headwinds and tailwinds for these reforms here.

Sometimes you’ll see third grade retention presented in some kind of scandalous fashion: “Some students get an extra year before they are tested!”

I ask: So what? Shouldn’t schools do whatever it takes, including adding an extra year of instruction, to make sure kids are reading successfully once they get to fourth grade, where the curriculum expects students to be able to read content across subjects? The measure of success is “proficient readers by 4th grade, not “proficient readers by age ten and a half.”

More issues with the Skeptics’ paper:

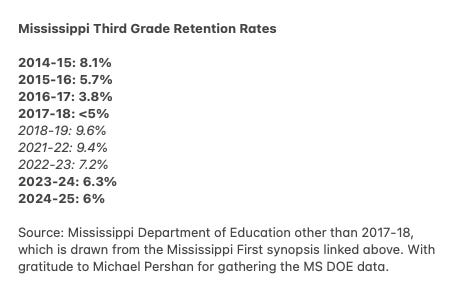

The Skeptics present only three years of retention data to illustrate their concern. Yet they show atypically-high retention years (the ones in italics below). Mississippi’s third grade retention rates peak in 2019, after state leaders raised the proficiency threshold, and remain high post-pandemic; retention rates settled down in the years that followed*:

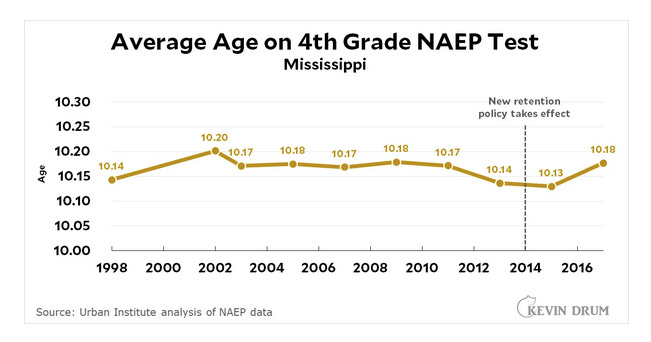

The 2013 legislation didn’t drive meaningful increases in retention rates in the first place. Mississippi’s average test-taking age didn’t jump after the 2013 legislation, as you’d expect in a state retaining a similar share of students before and after the 2013 law.

All of this nuance is missing from the Skeptics’ paper. The authors make no attempt to explore the dozen or so states that passed retention laws without seeing a jump in 4th grade reading scores.

Most of the paper finds the Skeptics sharing other promising growth stories that turned out to be frauds, so Mississippi’s must be, too. They note that Mississippi hasn’t produced 8th grade reading gains. Mississippi has actually risen a bit in the 8th grade rankings, but 8th grade ELA progress is well below 4th grade. Close watchers can explain the lagging 8th grade results: Mississippi’s work has focused–some would say overfocused–on early grade skills (phonics), while other aspects of literacy received lesser and later attention. Mississippi tried to course-correct with 2019 curriculum reforms, but the execution has been mixed (an issue common to most states, including Ohio and Georgia). None the less, Mississippi’s 8th grade improvement opportunities don’t invalidate its 4th grade progress.

From the Urban Institute (sorted by 8th grade reading):

Outstanding, fact-based pushback [disconfirmation] that models the kind of debates we need about American Education.

The other thing I really admire about the Southern playbook is the attention on birth-5 support systems for building language in the home. TN's program (GELF) that sends a monthly free book to households is a great example of this.