Curriculum mandates are trending, with movement in MA and MI. Should they be?

Massachusetts is poised to implement curriculum mandates, as legislation advances. Michigan wants to follow. Should we boost these efforts or pump the brakes?

On the state policy front, curriculum mandates are trending, and this week brought two updates.

The big news was in Massachusetts, where the senate advanced a bill which would curb local control on curriculum and require districts to select off a state list. Building on unanimous support in the House, this bill seems poised to become law.

In Michigan, the Department of Education asked legislators for similar rights, as well as mandatory LETRS training for teachers (don’t get me started about that1).

Massachusetts and Michigan would follow Ohio, where 2023 legislation introduced mandatory use of a state-listed program starting in 2024-25.

Should we get behind these mandates? It depends on the state of state leadership.

The Leadership Litmus Test

State leaders must navigate a challenging landscape, as readers of this Substack will know.

The curriculum review landscape is messy, reflecting divisions in the field, so state leaders face mixed signals. We also lack adequate data on curriculum efficacy.

Curriculum options are ever-changing. New programs debut each year; today, Great Minds, Lucy Calkins, and HMH are all introducing new reading materials. The most viral phonics program in the country (UFLI) is only 3-4 years into the field.

There are vigorous debates about the best dosage and model for phonics instruction (linguistic phonics vs traditional print-to-speech phonics) which have yet to be truly translated to the curriculum selection realm (though I expect that to change, which will evolve the picture further).

Savvy state leaders have navigated this effectively. Louisiana and Tennessee were pioneers, and saw reading outcomes rise after making book-rich, knowledge-building curriculum a statewide norm and supporting teachers on implementation.

Regrettably, savvy state leadership isn’t a given.

Massachusetts Mojo is Welcome

I have cheered the Massachusetts law because all evidence suggests that its state leaders have the capacity to craft a strong list, and Balanced Literacy curricula remain rooted in Massachusetts, sometimes to an irrational degree.

As I detailed in November, the current Massachusetts state list isn’t perfect, but it’s better than most, and everyone expects the bills to spawn new & improved lists. Also, the state literacy team seems to “get it,” judging by their creative grant programs and solid professional learning. The bill gives the team room to pivot from the EdReports model (educator review teams) to a better approach.

I see two additional reasons to support this bill:

First, the Senate version version of the bill leans more into the importance of oral language development in early years. Mike Moriarty of One Holyoke praised that development as a sign that the Senate “gets it,” and I concur.

Also, Massachusetts leaders have shown that they won’t be swayed by lobbying. Lucy Calkins was spied rallying her contacts in the districts of senators on the Senate Ways & Means committee:

Her letter was grossly inaccurate in its cost assertions (partly because some districts already use quality programs, and would not need to change). In any case, the bill passed in committee 12-0, so Massachusetts leaders seem united behind the need for change.

I have one point of caution on the legislation. The Senate bill calls for the development of a free, open source curriculum, to address concerns about costs. Louisiana created a free comprehensive reading program (Guidebooks), and while its development took years (one point of caution), it’s widely-used. BUT, it’s important to note that books are important in ELA curriculum, and quality books don’t come free. If this aspect of the bill survives, the language should leave room for free lesson materials to be designed around authentic trade books, not free passages. A passage-heavy program would lower cost to districts, but also lower quality and cut against the worthy oral language development goals in the Senate bill2.

Bill authors might also consider getting prescriptive about how the list is created, perhaps requiring a mixed panel of experts and experienced educators. A similar model was effective in Wisconsin.

I’m cheering this bill, and my reason has a name: Katherine Tarca. As the literacy lead in Massachusetts, she has the kind of savvy we saw in John White, Whitney Whealdon, Penny Schwinn, and Lisa Coons, the leaders in LA/TN. That’s what it takes.

Ohio and Georgia Offer Cautionary Tales

Other states haven’t had such savvy leadership.

Ohio was the latest state to implement curriculum mandates, and its initial list was seriously flawed. Under pressure, state leaders expanded the list to address some glaring issues, giving districts 21 options. Does anyone think that twenty-one curricula represent a tight curation?

Ohio’s final list basically said to districts: “You need to use a curriculum, and it can’t be Fountas & Pinnell or TCRWP Units of Study, but other than that, anything goes!” If the goal is just to get Balanced Literacy curricula out of classrooms, it would be easier to do so as a ban on certain programs than to create a mixed bag list.

Georgia proves my point, demonstrating that districts choose the weakest options off mixed-quality lists.

Really, everything hinges on the ability of state leaders (or their designated committees) to create tight lists at the highest quality bar, and evolve them as the landscape shifts.

Michigan Should Pump The Brakes

Michigan’s current curriculum list tells us that the state isn’t ready for mandates. It’s a mixed bag of foundational skills programs and comprehensive programs, for starters. Structurally, it fails to encourage districts to select materials for reading comprehension and writing; apparently, a “Phonics Patch” is good enough.

When Michigan did evaluate comprehensive programs, it screened for knowledge-building, according to the rubric. Yet Michigan gives Into Reading an 11/12 on that measure. The experts at the Knowledge Matters campaign think otherwise. Heck, teachers are writing blogs to illustrate the knowledge-building shortcomings of Into Reading. Michigan misses the mark.

Overall, I can’t support the idea that Michigan’s DOE has the chops to create a strong curriculum list.

Further, its continued embrace of LETRS training, years after Mississippi stopped using it, says: Michigan’s DOE isn’t keeping up with the times3.

The legislature should pass on the DOE’s requests, and it should look at upgrading the DOE’s own capacity.

Literacy Leaders As Linchpin

I’m sorry to be talking out of both sides of my mouth, but truly, leadership is the linchpin. Today, it’s in short supply in many state education departments. Judging by the state of state lists, more Ed departments look like Michigan’s than Massachusetts’s.

Worse, we lack an accountability mechanism to make these variations in state execution and capacity clear. Really, is there anything beyond this humble Substack pointing out these state list shortcomings? Getting into state execution on teacher training4?

This week, Rahm Emanuel, Andy Rotherham, and others nudged policymakers to step up their literacy game. I’m with them! But we have to get the details right if we want more Surges and fewer stalls.

Note about this Substack: I’m going to start publishing more ‘short and sweet’ update posts, to share breaking news with the field. It’s my reaction to the death spiral of the content in Twitter/X. I still post there, but hoo boy, the algorithm is grim right now, and I’d like to see a revival of EduTwitter somewhere.

As post frequency goes up, please delete rather than unsubscribe, y’all!

In my Drafts folder, there is a long post explaining why states need to move away from LETRS training as their norm, as Mississippi has already done.

At 150 hours, LETRS is simply too long and intensive for statewide training efforts.

Further, we keep seeing studies showing that it doesn’t translate to student gains, probably because it’s heavy on theory, and teachers need more tangible training, and more importantly good curriculum, to translate all the theory into their practice.

This recent study is merely the latest with the same finding:

Students’ third-grade reading achievement did not statistically differ for schools that adopted LETRS compared with other professional development experiences in any model, suggesting that LETRS was comparable to the other programs at improving third-grade reading achievement at the school level.

If a teacher training is long and expensive but doesn’t translate to student gains, why on earth is it so rooted in states like Michigan? How are they missing this memo?

I have tried to capture the state training approaches to follow in my piece on the Southern Surge:

On teacher training: we shouldn’t miss the shift away from LETRS, the training that practically became synonymous with the “Misssissippi Miracle,” to more streamlined, tangible training. LETRS training is 150 hours. Mississippi’s current AIM Pathways training is 45 hours. Tennesssee’s homegrown training was 60 hours. Louisiana requires 55 hours of training (from short list of providers). Asking teachers to take 150 hours of training is a LOT, and I have spoken with state leaders who hesitate about training mandates because they believe LETRS is the only option. We need to get the memo about alternatives to state and district leaders, alike.

I’ll try to finish the longer piece on LETRS soon, because there is more to say, on teacher concerns and the ways in which LETRS content sends outdated signals to teachers.

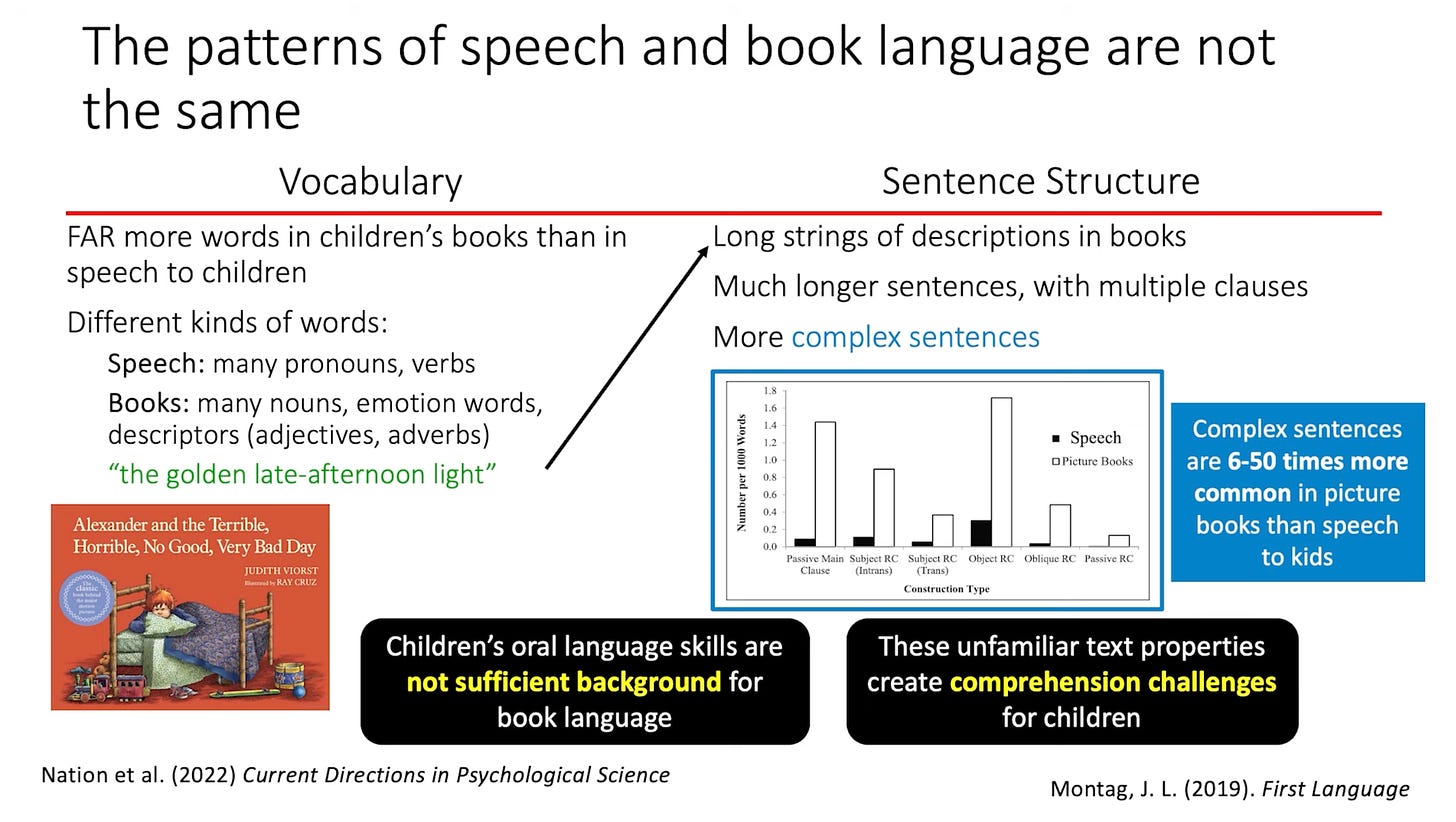

I just watched a fantastic presentation on the role of books in oral language development by psycholinguistics researcher Maryellen Macdonald, alongside Mark Seidenberg, who also hits important notes on foundational skills dosage and on the importance f background knowledge.

Here’s an excerpt and slide that should be essential reading in the curriculum conversation:

In books, “writers are sharing extensive information. They’re describing the scene, the characters, the actions, the feelings.

Nonfiction books, also huge amounts of information. And it’s not just more words in the book, though it certainly is that — it’s a different way of using language...

There are different estimates about this, but let me just say there are far, far more words. in children’s books than in the speech to children.

You can see that, obviously, you read a book about a hippo, there’s going to be all sorts of hippo-associated words, but the daily life of a child doesn’t have deep discussions about hippo. So 50% more, 80% more, I mean, many, many more words…

You get these long strings of descriptors in books that you don’t get in speech, “golden late afternoon light” being one. Here’s another classic example. Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day…. you get much longer sentences in books than the way we talk.

In studies, complex sentences are 6-50 times than in the speech to kids. Kids could go a week and never hear some of these structures and yet encounter them four times in a book that somebody is reading to them.”

If you want oral language development, you must insist on books in elementary classrooms.

On LETRS, read footnote #1 above.

Yes, I know about the ExcelInEd tracker. Go check out its consistent stumping for LETRS training, read footnote #1 above, and you’ll understand why I don’t think it’s meeting the moment. That’s just one of its shortcomings; it also gives shallow treatment to curriculum quality nuances, in an era when everyone knows that “HQIM” as defined by EdReports is a flawed measure. Plus its model effectively gives states participation trophies for taking action, even if their test scores show a five year decline. It’s a worthy effort, and I’m glad it exists to give us a window into state effort, but it is mired in “Just Do Mississippi’s V1 Work”-think, and a failure to ground the work in actual outcomes.

Thank you, Karen. I’ve been really trying to understand the pros and cons of the MA legislation. As a parent of young children in a Units of Study district, my instinct is this can’t come soon enough. The MA Teachers Association strongly opposes the bill, and I recently attended a webinar they hosted to try to gain understanding of their perspective. I am glad to read that you support MA moving forward with this, and I feel more confident in standing behind it after reading this.

"There are vigorous debates about the best dosage and model for phonics instruction (linguistic phonics vs traditional print-to-speech phonics) which have yet to be truly translated to the curriculum selection realm." This is REALLY important: finding efficiency as well as effectiveness. I wrote about it in Timothy Shanahan Points to a Possible Speech-to-Print Advantage (https://harriettjanetos.substack.com/p/timothy-shanahan-points-to-a-possible?r=5spuf). Thanks for highlighting this!