A call for a national curriculum database

We desperately need a window into curriculum use in American schools. I'm begging Linda McMahon or Congress to rescue us from our confusion.

Recently, the Fordham Wonkathon sought the field’s best ideas for making Science of Reading laws work. Here’s mine:

We need a national curriculum database, published openly and updated annually, to finally offer insight into district curriculum selections. Today, that landscape is incredibly opaque—but it doesn’t need to be.

Imagine a world where we could run regression analyses to see the impact of curriculum change on district performance. Or we could compare the aggregate performance of districts using curriculum with and without whole books, or basals vs knowledge-building materials. Imagine being able to see which programs are associated with district overperformance—and underperformance.

With the right data collection, it’s possible.

Here’s why we need this so badly, and how to get it done.

The country has woken up to the fact that curriculum matters.

Emily Hanford helped establish that weak curricula can usher weak practices like cueing into schools. Poor curriculum choices also lead to in ELA classrooms without books. Curriculum really matters.

If curriculum can bring weak instruction into schools, it stands to reason that it can spawn better instruction, too.

In recent years, multiple studies1 have shown improved outcomes from use of book-rich, knowledge-building curricula.

Louisiana and Tennessee brought strong curricula into use statewide, and reading score improvements followed. It’s a powerful illustration of the possibilities.

Yet states aren’t exactly rushing to follow Louisiana and Tennessee. Districts aren’t, either; nationally, knowledge-building and book-rich programs have weaker market share than the alternatives.

What’s blocking progress?

The field remains divided on the essentials of reading instruction.

We’ve finally settled the “reading wars,” and everyone agrees that schools should be teaching phonics systematically. That’s the good news.

Yet debates continue to rage. Folks vigorously debate nuances, like small group versus whole class phonics instruction and speech-to-print vs print-to-speech approaches. Many embraced a faddish approach to phonemic awareness, popularized by David Kilpatrick and baked into the viral Heggerty materials. Even in the Science of Reading era, schools have made not-so-sciencey choices.

When it comes to reading comprehension, most of the field is behind-the-curve in understanding the role of knowledge to reading comprehension and the implications for curriculum. Even prominent literacy organizations don’t always get it, as you can see from curriculum review efforts.

We’re in the upside-down, unable to get literacy leaders to agree on the need for books in curriculum.

I describe this as our Implementation Wars era: the old debates have given way to new ones. And frankly, today’s questions are a lot more complicated than “should you teach phonics or not?”

If you think these Implementation Wars will resolve themselves quickly, I’d like to remind you that the Reading Wars lasted ~80 years. We need better lenses on the open questions in order to see progress in my lifetime.

Because of these debates…

We lack reliable guideposts on curriculum quality.

Multiple curriculum review efforts look at materials from different vantage points, and come to sometimes-conflicting conclusions.

Critically, EdReports, the dominant review source, lost its way. It’s going through a leadership transition, and improvements will come slowly.

State curriculum lists are a mess, because most states followed EdReports. We’re starting to see lists that mash-up multiple review sources, and they basically illustrate the confusion.

Efficacy research is limited.

Studies on curriculum effectiveness are few and far between. In part, this is because they’re costly. Also, there is no “FDA for Education” demanding research into products used in schools.

Districts don’t demand solid evidence, either, so publishers have little incentive to invest in efficacy studies.

In addition, education researchers tend to create their own materials for their research efforts, rather than doing trials on the stuff actually used by schools2.

There’s painfully-little tracking of curriculum used in schools.

Would you believe that only a handful of states publish the curriculum used in each district, and only periodically?

So, if researchers wanted to analyze outcomes by curriculum, they have very little to work with.

A national database would be a godsend.

With the stroke of a pen and small project, the US Department of Education could address this problem. Alternately, congress could step up with transparency requirements.

Either way, here’s what I’d like to see:

First, a mandate that districts report on the curricular materials used in K-12 ELA and math, for this school year and the last two school years, into a central national database.

The part about the last two years is important, and reasonable. We need to create a historical record of which curricula were used in which years, so we can track trends over time.

The Department of Education would need to create the database (which would be reasonably light work, actually3), and of course enforce the expectation.

Then, the info should be published openly, as a national data set accessible to researchers and families alike. And it should be collected annually, for at least the next 3 years, so we get a six-year, national data set.

I see two big benefits:

Analysis potential: We would empower the research community to produce insights on the role of curriculum in district outcomes, during an era of significant switching by districts. There is demand for this info; I’ve had multiple researchers ask me for information on curriculum usage and market share for various programs. Many people would like answers.

Transparency: As the saying goes, “what gets measured gets done.” In this case, I’d say: what gets reported can finally get focused attention. Today, it’s hard for anyone (journalists, families) to find information about curriculum selections on district websites. (For the record, I also support transparency mandates for districts, requiring them to list curriculum selections on the homepage of district and school websites.) If we know curriculum matters, let’s get sunlight on these selections.

This idea fits the administration’s MO

In K-12, Linda McMahon has been inclined to leave power to the states. That has downsides in a country where many states are currently failing to closely follow the Southern Surge leaders on literacy. Nonetheless, it’s the reality, and I’m a pragmatic girl.

In higher education, probes have been policy during McMahon’s tenure. As her former counsel put it, “This has been a year of enforcement through investigation.” McMahon could apply her spirit of targeted inquiry to K-12 curriculum choices.

Mind you, this vibe has raised some hackles. And I wouldn’t want to see this idea fall victim to efforts to create culture wars about the way that history is taught, etc. So, one could argue this idea is better served by congressional action (best of all if it’s bipartisan). With Rahm Emanuel shouting out curriculum reform states Louisiana and Tennessee in his social media posts, we’re seeing literacy interest from the left and the right, and it should mojo from presidential aspirants (although I hope we don’t have to wait until the next election cycle(s) to get traction on a database).

Congress has a weak recent legacy on K-12 education, beyond sending dollars its way, so I write this post assuming McMahon is more likely to be the first mover. It’s anyone’s guess, though.

All parties seem wedded to local control norms, or at least afraid to question them. Transparency requirements don’t challenge local control. Their message is: We’re not going to tell you what curriculum to use. But we are going to demand that you make your choices public. If you spend public dollars on programs, the public deserves to know what you bought. Oh, and if you decided not to purchase programs, and instead pushed curriculum development to your staff, we should know that, too.

Also… please Linda McMahon or Congressional bill-drafters, for the love of God, do not take this idea and push it down to the states, as a mandate for each state to execute individually. States will slow-walk it. More importantly, they will produce inconsistent data sets which make the work harder for everyone. Sometimes, like the NAEP, there is a role for standardized federal collection of valuable data. This is one of those times.

We gotta cut through the confusion.

The noisy, opaque curriculum quality landscape serves no one.

We need better signals to help districts navigate curriculum selection and to aid policymakers and parents in understanding the options.

And we’re overdue to bring the conversations about curriculum quality over to math. A national data collection effort would kick-start those conversations, I’m sure.

Absent better data signals, I fear we’ll remain mired in debates about what works and what doesn’t.

It bears restating: the Reading Wars raged for eighty years. The Math Wars never paused. A national curriculum database is our best hope for skipping ahead in today’s Implementation Wars.

The evidence base for knowledge-rich curriculum, and its role in reading improvement, is so strong, it’s hard to believe there are still naysayers, but I guess I’m learning why we have reading wars.

Here are highlights:

Grissmer, Willingham, et al (2023): Researchers studied outcomes for students randomly assigned to charter schools using Core Knowledge Language Arts (CKLA), a knowledge-building program, versus a comparable student cohort. Students in CKLA schools outperformed the other cohort in reading (ES 0.24–0.47) as well as science ES = 0.15–0.30). Most students were in middle-to-upper-class demographics; however, one charter was in a low-income district, where even larger effect sizes were seen for students from low-income backgrounds [albeit with a small sample size for this subgroup].

Cabell (2020): Students who received one semester of ELA instruction using the Core Knowledge Language Arts curriculum outperformed comparison students on measures of reading comprehension, knowledge, and vocabulary.

James Kim (2023): Researchers developed a content literacy intervention to build domain and topic knowledge in science for first and second grade students. Reading comprehension improved for students in the treatment group (ES = .18) over students in the control group, who received business-as-usual instruction.

Grey (2021): Urban kindergarteners who received one year of instruction with the knowledge-building ARC Core curriculum performed better than a comparison group in reading comprehension (ES = .17). Researchers also reported increases in children’s motivation to read (ES 0.32).

Tyner (2020): Researchers analyzed data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, and found that students who spend more instructional time on Social Studies perform better on reading comprehension. More instructional time in ELA was NOT correlated with higher performance on reading comprehension. Effects were highest for least privileged students.

May, Walpole et al (2023): Researchers studied the performance of second through fifth graders in 17 elementary schools across three school years and estimated an effect size of .26 from work with the Bookworms curriculum, which has the largest volume of books of any curriculum in the US, while also being designed for knowledge and vocabulary exposure. Effects compounded with each year.

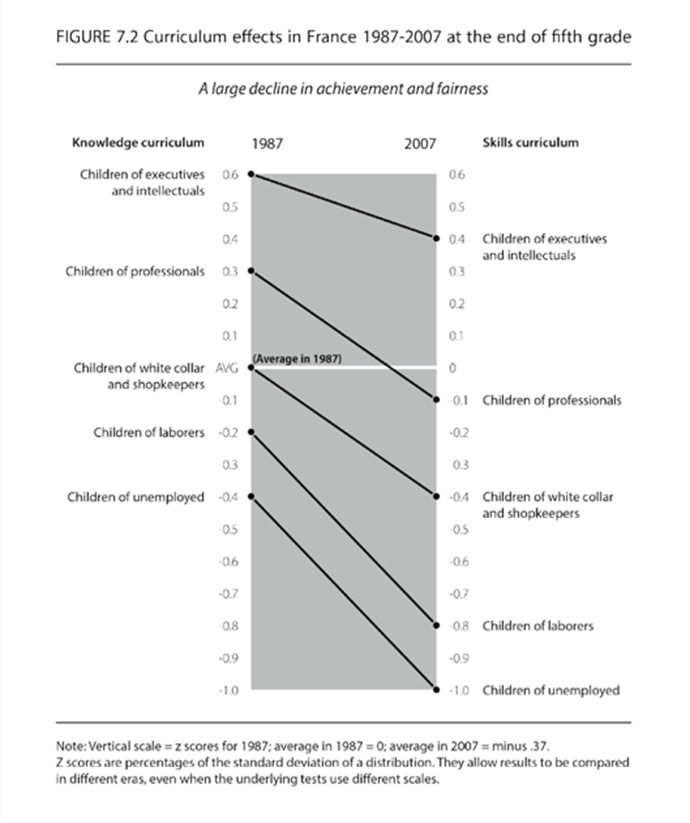

French national reading outcomes, 1987-2007: E.D. Hirsch references the national outcomes in France, which saw declines in reading outcomes after switching from a national curriculum designed for knowledge acquisition to a skills-based curriculum. Declines were most pronounced for the least privileged children:

Source: Why Knowledge Matters by E.D. Hirsch

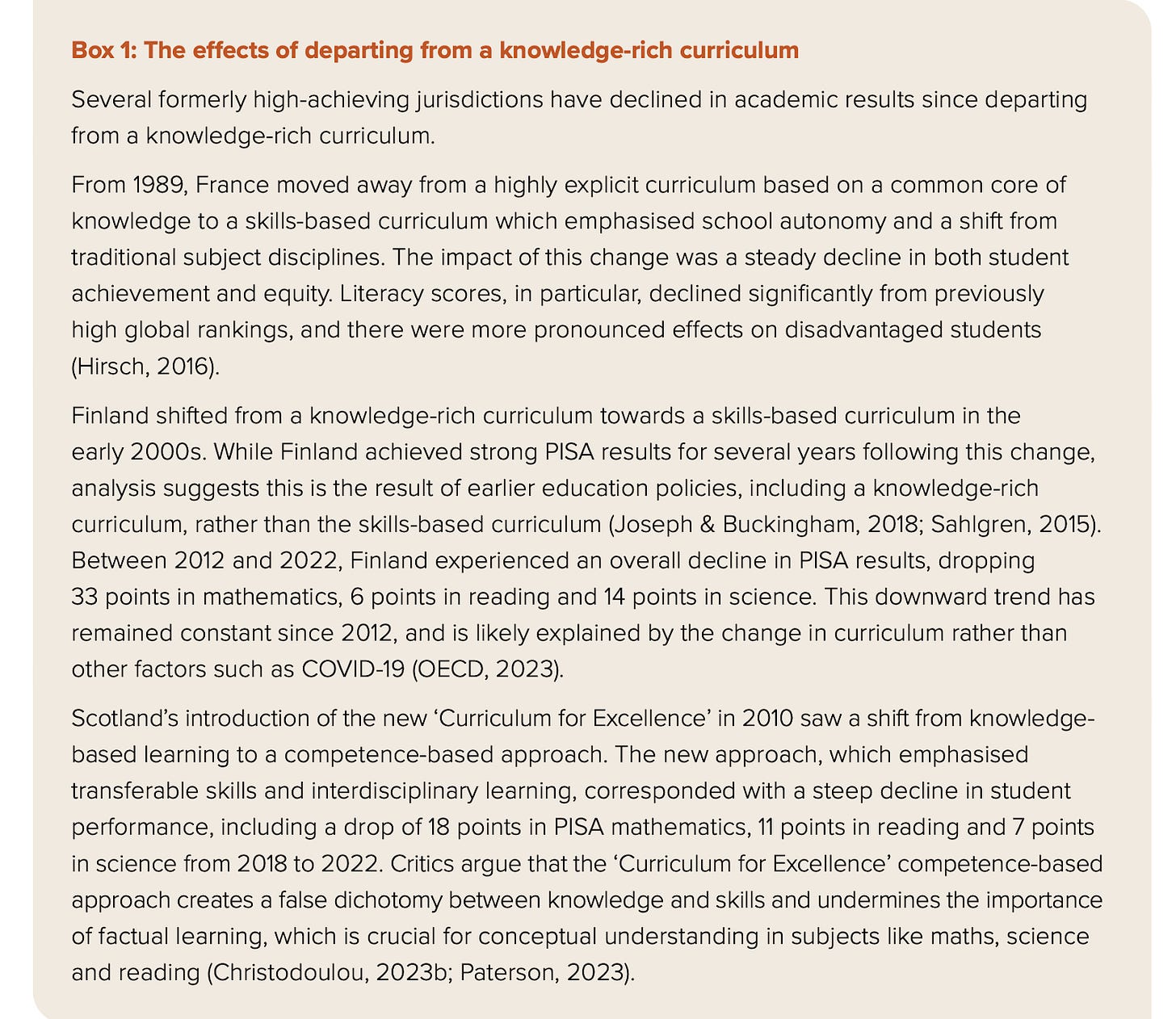

AERO also references the historic experience in Scotland and Finland. In both countries, like in France, a change from a knowledge-centered curriculum to a skills-oriented curriculum was followed by declines in reading achievement:

It wouldn’t hurt to change these norms. I appreciate Jimmy Kim’s study, listed above. But I know that Sonia Cabell’s research, on programs schools can actually purchase, has better potential to change school behavior. Grantmaking organizations should prioritize research on existing materials in order to close the research-practice divide.

During the pandemic, Emily Oster swiftly stood up a database to collect weekly data on COVID case rates. Her effort was independent of the Department of Education, but supported by superintendents’ and principals’ groups, and she made real impact with her data.

I appreciate that some thoght would need to go into the database structure, in order to account for use of multiple curricula per grade band (ex. different foundational skills and comprehension curricula in ELA). And schools would need to be able to indicate the use of district-created materials, as they could in the Massachusetts survey.

I’d give the effort extra credit if we asked for estimates of the length of the ELA and math blocks, and also the amount of daily time spent on tech-enabled products. And if districts were asked to note the providers of any curriculum-aligned professional learning.

If Linda McMahon wants help designing the database, I volunteer as tribute.

But even the most expansive survey I can conjure should be something a district curriculum leader could complete in an afternoon for all three years in the initial data set.

I think it’s reasonable to ask district leaders to do a few hours of data entry to empower important national insights. Don’t you?

I totally agree that we need better data on curriculum, and for the reasons you outline, it probably makes sense for the federal government to collect it. Although I have to say, I'm wary of having THIS administration collect the data, because the effort may be perceived by some states and districts (i.e., blue ones) as an attempt to police the concepts and texts that are being taught.

My other concern is that even in districts that have been using effective knowledge-building curricula, many teachers are apparently responding to data from benchmark testing by modifying those curricula so that they focus on superficial, skills-driven instruction. That's what a recent SRI study of several such districts found. (See my post at https://nataliewexler.substack.com/p/using-knowledge-building-curriculum). So you could have a database showing little progress in many districts using knowledge-building curricula, and the reason -- ineffective implementation -- would be obscured.

Yes, Karen. Evaluating the curriculum is the first step to adopting the successful programs. The teacher training probably be in the mix. Good job advocating for our students and understanding metrics should the way to improve declining literacy in the United Stated.